Python vs. Scala: a comparison of the basic commands (Part I)

I recently started playing a little bit with Scala, and I have to say it has been kind of traumatic. I love learning new things but after months of programming with Python, it is just not natural to set that aside and switch mode while solving Data Science problems. When learning a new language, whether it is a coding or a spoken one, it is normal for this to happen. We tend to fill in the gaps of the things we don’t know with the things we know, even if they don’t belong to the language we are trying to write/speak! When trying to learn a new language, it is important to be completely surrounded by the language you want to learn, but first of all, it is important to have well established parallelisms between the known and the new language, at least in the beginning. This works for me, a bilingual person who learned a second language really quickly, at an adult age. At the beginning, I needed connections between Italian (the language I knew) and English (the language I was learning), but as I became more and more fluent in English, I started to forget the parallelisms because it was just becoming natural and I didn’t need to translate it in my head first, anymore. The reason why I decided to write this post is, in fact, to establish parallelisms between Python and Scala, for people who are fluent in one of the two, and are starting to learn the other one, like myself.

I initially wanted to focus on Pandas/Sklearn and Spark, but I realized that it doesn’t make much sense without covering the foundations first. This is why in this post we’ll look at the basics of Python and Scala: how to handle strings, lists, dictionaries and so on. I intend in the near future to publish a second part, where I will cover how to handle dataframes and build predictive models in both languages.

1. First things first

The first difference is the convention used when coding is these two languages: this will not throw an error or anything like that if you don’t follow it, but it’s just a non-written rule that coders follow.

When defining a new variable, function or whatever, we always pick a name that makes sense to us, that most likely will be composed by two or more words. If this is the case, in Python we will use snake_case, while in ScalacamelCase: the difference is immediately noticeable. In snake case, all words all lower-case and we use _ to separate them, in camel case there is no separation, and all words are capitalized except for the first one.

Another striking difference is how we define the variables in the two languages. In Python we just make up a name and assign it to the value we need it to be, while in Scala, we need to specify whether we are defining a variable or a value, and we do this by placing var or val respectively, before the name (notice that this is valid whether we are assigning numerical values or strings).

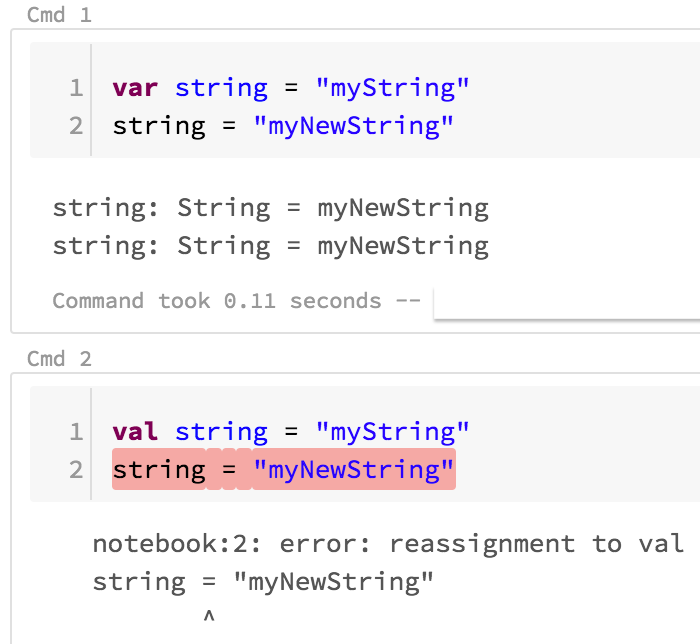

Initializing values and variables in Scala.

The difference between var and val is simple: variables can be modified, while values cannot. In the example represented in the image, I instantiated avar string and then changed it: all good. Then, I assigned the same string to a val and tried to change it again: not doable.

In Python there is no need to specify: if you want to change something you previously assigned, it’s up to you. In Python’s case I would just dostring = 'my_string'.

Another general difference regards commenting. In Python there is only one way to do it, whether it’s a single or multi-line, and that is putting a # before the comment, on each line:

# this is a commented line in Python

Scala offers a couple of ways to comment, and these are either putting // on each line, or wrap the comment between /* and */:

// this is a commented line in Scala

/* and this is a multiline comment, still in Scala...

...just choose! */

Now that the very basics are explained, let’s see dive deeper.

2. Lists and arrays

List (in Python) or Array (in Scala) are among the most important objects: they can contain strings and/or numbers, we can manipulate them, iterate over them, add or subtract elements and so on. They can basically serve any purposes, and I don’t think I have ever coded anything without using them, so let’s see what we can do with them, and how.

2.1. Define

Let’s create a list containing a mix of numbers and strings.

my_list = [2, 5, 'apple', 78] **# Python**

var myArray = Array(2, 5, "apple", 78) **// Scala**

/* notice that in Scala I wrapped the string between “”, and that is the only way to do it! In python you can use both “” and “ indifferently */

2.2. Indexing

Both lists and arrays are zero indexed, which means that the first element is placed at the index 0. So, if we want to extract the second element:

my_list[1] **# Python** uses [] to index

myArray(1) **// Scala** uses () to index

2.3. Slicing

In both languages, the second index will not be counted when slicing. So, if we want to extract the first 3 elements:

my_list[0:3] **# Python** slicing works like indexing

myArray.slice(0,3) **// Scala** needs the .slice()

2.4. Checking first, last, maximum and minimum element

**# Python**my_list[0] # first element

my_list[-1] # last element

max(my_list) # maximum element

min(my_list) # minimum element#

NOTE: min() and max() will work exclusively if the list contains

# numbers only!**// Scala**myArray.head // first element

myArray(0) // other way to check the first element

myArray.last // last element

myArray.max // maximum element

myArray.min // minimum element/*

NOTE: .min and .max will work exclusively if the array contains numbers only!*/

2.5. Sum and product

These operations, as for min and max, will be supported only if the lists/arrays contain exclusively numbers. Also, to multiply all the elements in a Python’s list, we will need to set up a for loop, which will be covered further down in the post. There is no preloaded function for that, as opposed to Scala.

sum(my_list) # summing elements in **Python**'s list

// **Scala**

myArray.sum // summing elements in array

myArray.product // multiplying elements in array

2.6. Adding elements

Lists and arrays are not ordered, so it’s common practice to add elements at the end. Let’s say we want to add the string "last words":

my_list.append('last words') # adding at the end of **Python**'s list

myArray :+= "last words" // adding at the end of **Scala**'s array

If, for some reason, we want to add something at the very beginning, let’s say the number 99:

my_list.insert(0, 99)

# this is a generic method in **Python**. The

# first number you specify in the parenthesis is the index of the

# position where you want to add the element.

# 0 means that you want the element to be added at the very

# beginningmyArray +:= 99 /* adding an element at the beginning of **Scala**'s array */

3. Print

This is also something that we use all the time while coding, luckily there is a only a slight difference between the two languages.

print("whatever you want") # printing in **Python**

println("whatever you want") // printing in **Scala**

4. For loop

Quite a few differences here: while Python requires indentation to create a block and colon after the statement, Scala wants the for conditions in parenthesis, and the block in curly brackets with no indentation needed. I like to use indentation anyway though, it makes the code look neater.

# for loop in **Python**

for i in my_list:

print(i)// for loop in **Scala**

for (i <- myArray){

println(i)

}

5. Mapping and/or filtering

All things that, in Python, can be done by using list comprehensions. In Scala we will have to use functions.

5.1. Mapping

Let’s say we have a list/array with only numeric values and we want to triple all of them.

[i*3 for i in my_list] # mapping in **Python**

myArray.map(i => i*3) // mapping in **Scala**

5.2. Filtering

Let’s say we have a list/array with only numeric values and we want to filter only those divisible by 3.

[i for i in my_list if i%3 == 0] # filtering in **Python**

myArray.filter(i => i%3 == 0) // filtering in **Scala**

5.3. Filtering and mapping

What if we want to find the even numbers and multiply only them by 3?

[i*3 for i in my_list if i%2 == 0] # **Python**

myArray.filter(i => i%2 == 0).map(i => i*3) // **Scala**

6. Dictionaries/Maps

Although they have different names in the two languages, they are exactly the same thing. They both have keys to which we assign values.

6.1. Create dictionary/map

Let’s create one storing my first, last name and age… and let’s also pretend I am 18.

# **Python**

my_dict = {

'first_name': 'Emma',

'last_name': 'Grimaldi',

'age': 18

}

In Scala we can do this in two different ways.

// **Scala** mode 1

var myMap = (

"firstName" -> "Emma",

"lastName" -> "Grimaldi",

"age" -> 18

)// Scala mode 2

var myMap = (

("firstName", "Emma"),

("lastName", "Grimaldi"),

("age", 18)

)

6.2. Adding to dictionary/map

Let’s add my Country of origin to my dictionary/map.

my_dict['country_of_origin'] = 'Italy' # creating new key in **Python**

myMap += ("countryOfOrigin" -> "Italy") /* creating new key in **Scala** */

6.3. Indexing

This works the same way as indexing lists/array, but instead of positions, we are using keys. If I want to see my first name:

# **Python**

my_dict['first_name']/

/ **Scala**

myMap("firstName")

6.4. Looping

If we want to print the dictionary/map, we will have to for loop in both cases, over keys and values.

# Python

for key, value in my_dict.items():

print(key)

print(value)// Scala

for ((key, value) <- myMap){

println(key)

println(value)

}

#

7. Tuples

Yes, they are called the same in both languages! But, while they are zero-index in Python, they are not in Scala. Let’s create a tuple (1, 2, 3) and then call the first value.

# Python

my_tup = (1, 2, 3)

my_tup[0]

# the indexing is the same as lists// Scala

myTup = (1, 2, 3)

myTup._1

// the indexing is way different than arrays!

8. Sets

Yes, another name in common! In both examples below, the sets will contain only 1, 3, 5 because sets don’t accept duplicates.

my_set = {1, 3, 5, 1} # in **Python**, sets are defined by curly braces

mySet = Set(1, 3, 5, 1) // **Scala**

9. Functions

We have covered a lot so far, good job if you made it down here! This is the last thing paragraph of this post, and luckily defining a function is not that different between Python and Scala. They both start with def and while the former requires a return statement, the latter does not. On the other hand, Scala wants to know what types of variables we are going to input and output, while Python doesn’t care. Let’s write a very simple function that takes a string as input and returns the first 5 characters.

# **Python**

def chop_string(input_string):

return input_string[0:5]

Indentation is also important in Python, or the function will not work. Scala instead just likes its curly braces.

// **Scala**

def chopString(inputString: String): String = {

inputString.slice(0, 5)

}

That’s it! I hope you found this helpful as an immediate reference for those of you who are just starting to get familiar with either Python or Scala. The following step will be to build a similar guide to explore the differences between pandas/sklearn and sparks, looking forward to it! I hope you do as well!

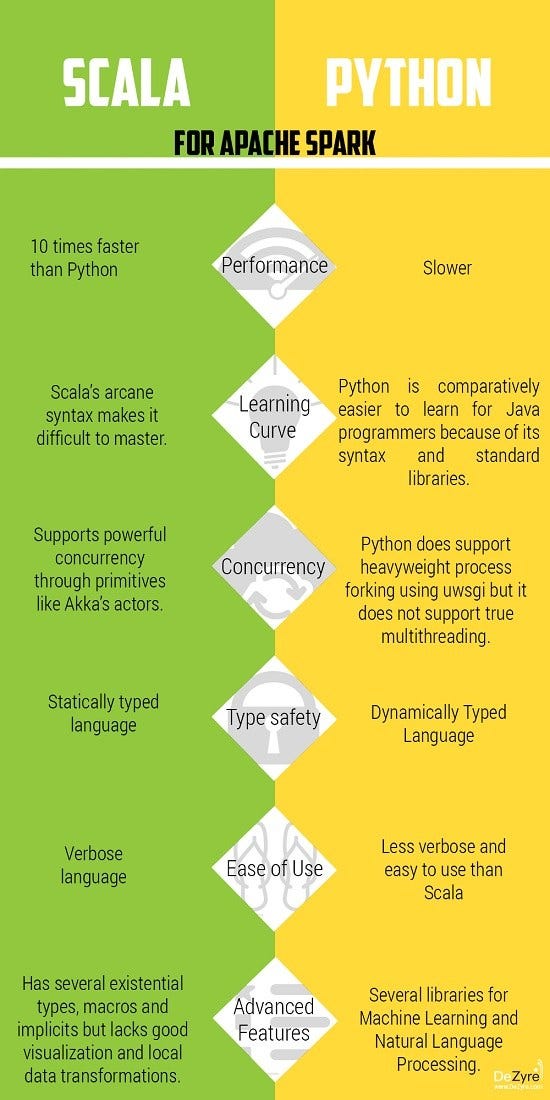

If you are wondering why you should use Python rather than Scala, or vice versa, I found the image below rather helpful in clarifying the immediate differences between the two.

Feel free to check out: